100

|

WILLIAM SEYMOUR

and the

AZUSASTREET REVIVAL

From Kansas in 1905, Charles Fox

Parham took a band of his protégés into Texas. There he preached,

distributed his The Apostolic Faith newspaper, won

converts, and set up a non-credit Bible school.

Parham’s Bible School in Houston, Texas

One of the students attracted to the

school was a former

waiter and southern Holiness preacher, William J. Seymour.

In the Jim Crow South, Seymour, a black, could take

part in the Bible studies only by sitting in the hallway

outside Parham's classroom.

After only a few weeks of

listening to Parham, Seymour received an invitation to

pastor a small Los Angeles church of Baptists expelled

from their congregation for espousing Holiness doctrines.

Seymour carried more than his luggage to California. He

boarded the steam train in the Houston depot with

enthusiasm and Parham's finely tuned statement of faith

The 35-year-old Seymour was

an unlikely ambassador of the Pentecostal message: he

was the son of slaves, not a gifted speaker, lacking in

social skills, had almost no formal education, and was

blind in one eye. But perhaps his greatest handicap was

the fact that he had never spoken in tongues, even

though he preached that such a sign should be a part of

every believer's experience.

He chose Acts 2:4 as the

text for his first sermon at the mission on Santa Fe

Street in Los Angeles: "And they were all filled

with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other

tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance."

His message, that speaking in tongues was the

"Bible evidence" of baptism in the Spirit, was

well received by the congregation but not by the

pastor, Julia Hutchins. It is unclear how long

she let Seymour teach such things, but she soon

had the door padlocked shut against him.

Seymour and most of the congregation found an

open door for ministry in the Edward Lee home

where he was boarding. The Lees and a small

group had been praying for a another Great

Awakening, a Welsh-type revival that would turn

Los Angeles upside down. And they believed that

Seymour might be the catalyst.

When the Lee home grew too small for the

interracial crowd that gathered for Seymour's

Bible studies and prayer meetings, Richard and

Ruth Asberry opened their home at 214 (now 216)

North Bonnie Brae Street, even though they then

disagreed with some of his teaching.

On April 9,

1906, Edward Lee asked Seymour to pray for

him that he would be given the gift of

tongues. When Seymour prayed, Lee spoke in

tongues, fulfilling a vision he said he had

received in which the apostles taught him

how to speak in tongues.

Seymour immediately left for the

Asberry home Bible study and prayer meeting,

where he again preached from Acts 2:4 and

related Lee's experience. As he continued

his study, someone else began speaking in

tongues. Others followed. Jennie Moore,

Seymour's future wife, sat down at the piano

and improvised a tune while singing what she

thought was Hebrew.

The meetings began at 10 a.m., and

continued for at least 12 hours, often

lasting until two or three the next morning.

Crowds of

both black and white faces descended on

the Asberry home over the next several

days. On April 12, the first white man

spoke in tongues. More importantly,

Seymour, "the prophet of Pentecost to

Los Angeles,"

finally received his

personal Pentecost.

And that

same day, the Asberry's front porch

gave way from the weight of the

crowds. That's when leaders

negotiated a lease for the former

Stevens African Methodist Episcopal

Church at 312 Azusa Street.

The

windows were knocked out. Debris

littered the floor. Its last

occupants had been livestock,

since it had most recently been

used as a stable.

It was more like the rustic

outdoor camps of the Holiness

movement than the

stained-glass churches of the

distrusted denominations. And

since it was not in a

residential area, meetings

could go all night.

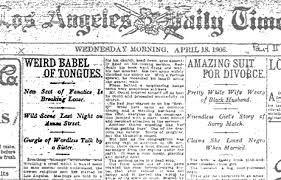

Within a week, a makeshift

pulpit, altar, and benches

graced what the Times

reporter called the

"tumble-down shack" where

"colored people and a

sprinkling of whites"

practice the "most fanatical

rites, preach the wildest

theories, and work

themselves into a state of

mad excitement in their

peculiar zeal."

The article, published

almost immediately after

the group's move to the

new church, took Seymour

to task, too: "An old

colored exhort [he was

only 35], blind in one

eye, is the majordomo of

the company," the

reporter wrote. "With

his stony optic fixed on

some luckless

unbeliever, the old man

yells his defiance and

challenges

an answer. Anathemas are

heaped upon him who

shall dare to gainsay

the utterances of the

preacher."

Although he

knew the Pentecostal

teaching would be

controversial, Seymour

was adamant about what

he had learned and

experienced. The Holy

Spirit, he said, "will

find pure channels to

flow through, sanctified

avenues for his power….

You will never have an

experience to measure

with Acts 2:4 … until

you get your personal

Pentecost or the baptism

with the Holy Ghost and

fire."

Let the tongues come

forth!"

By

September the church

reported that about

13,000 people had

"received this

gospel. It is

spreading

everywhere, until

churches who do not

believe backslide

and lose the

experience they

have. Those who are

older in this

movement are

stronger, and

greater signs and

wonders are

following them."

Though

there were periods

of silence in the

meetings, where even

the most

demonstrative

believers sat still,

most of the meetings

were electric, loud,

and unlike the

services of "any

company of fanatics,

even in Los Angeles,

the home of almost

numberless creeds."

The meetings began

at 10 a.m., and

continued for at

least 12 hours,

often lasting until

two or three the

following morning.

"Elder" Seymour

rarely preached,

but when he did,

he would often

take out a tiny

Bible and read

only one or two

words at a time.

Then he would

walk the room,

challenging

unbelievers face

to face,

shouting to

those kneeling

at altars to

"let the tongues

come forth!" or

"Be empathetic!“

There were no

hymnals, no

liturgy, no

order of

services. Most

of the time

there were no

musical

instruments. But

around the room,

men jumped and

shouted. Women

danced and sang.

People sang

sometimes

together, yet

with completely

different

syllables,

rhythms, and

melodies. At

other times the

church joined

together in

English versions

of "The

Comforter Has

Come," "Fill Me

Now," "Joy

Unspeakable,"

and "Love Lifted

Me." At various

places, some

would be "slain

under the power

of God" or

entranced.

"Proud,

well-dressed

preachers

come in to

'investigate,'

" informed

The

Apostolic

Faith (a

newspaper

founded by

Seymour, not

to be

confused

with

Parham's

publication

of the same

name). "Soon

their high

looks are

replaced

with wonder,

then

conviction

comes, and

very often

you will

find them in

a short time

wallowing on

the dirty

floor,

asking God

to forgive

them and

make them as

little

children."

Depending on

the

observer,

the

occurrences

were either

proof of

God's

presence or

of the

participants'

fanaticism.

But to all

witnesses,

it was

something

new.

'You-oo-oo

gou-loo-loo

come

under

the

bloo-oo-oo

boo-loo,'

shouts

an old

colored

'mammy'

in a

frenzy

of

religious

zeal,"

reported

the

skeptical

Times.

"Swinging

her arms

wildly

about

her, she

continues

with the

strangest

harangue

ever

uttered."

Despite

the

frequent

critical

news

reports,

the

curious

and

genuine

seekers

continued

to pour

down

Azusa

Street.

"The

secular

papers

have

been

stirred

and

published

reports

against

the

movement,"

boasted

the

first

issue of

The

Apostolic

Faith.

"But it

has only

resulted

in

drawing

hungry

souls

who

understand

that the

Devil

would

not

fight a

thing

unless

God was

in it."

In fact,

when the

Times

printed

a

speaker's

prophecy

of

"awful

destruction"

the day

of the

San

Francisco

earthquake,

many

residents'

interest

was

piqued.

One

striking

feature

of

the

early

meetings:

they

were

interracial.

Although

Los

Angeles

was

not

segregated

by

law,

it

was

unusual

in

the

growing

city

of

230,000

to

see

blacks,

whites,

Hispanics,

Asians,

and

newly

arrived

European

immigrants

worshiping

under

the

same

roof.

A

1906

Azusa

staff

photo

shows

blacks

and

whites,

men

and

women—all

in

leadership.

An

unsigned

article

in

the

November

1906

issue

of

The

Apostolic

Faith

said,

"No

instrument

that

God

can

use

is

rejected

on

account

of

color

or

dress

or

lack

of

education."

Another

described

one

Communion

service

and

foot

washing

that

lasted

until

daybreak:

"Over

twenty

different

nationalities

were

present,

and

they

were

all

in

perfect

accord

and

unity

of

the

Spirit."

Though reports of the miraculous were sometimes exaggerated, the church didn't mask the revival's problems. Seymour wrote several letters to Parham asking advice in dealing with spiritualists and mediums from occult societies, who were trying to conduct séances in the services. And the church publicly admitted that not everyone at the meetings felt the presence of the Spirit:

“ While some in the rear are opposing and arguing, others are at the altar falling down under the power of God and feasting in the good things of God. The two spirits are always manifest, but no opposition can kill, no power in earth or hell can stop God's work."

A future general superintendent of the Assemblies of God, Ernest S. Williams, drawn to Azusa Street from Denver, was turned off by the more fanatical elements, but he also sensed vitality:

"On the brink of turning away," he said, "a great check came over my spirit. Then I began to seek earnestly."

Chicago pastor William Durham was also somewhat skeptical of the meetings, having heard conflicting reports, but he reported, "As soon as I entered the place, I saw that God was there."

Many of the thousands who poured into 312 Azusa Street between 1906 and 1909 heard the revival news through the widely circulated The Apostolic Faith. The paper not only kept readers abreast of what was happening in the "City of Angels" but also in churches and mission stations around the world.

Whether the seekers read the paper or came in person, they were certain to receive messages emphasizing repentance, salvation, humility, worship, healing, deliverance from demonic possession, holy living, and the baptism in the Holy Spirit

Divisions and the end

Along with the success, hurts and heartaches soon came to Azusa Street. Seymour and the faithful learned to expect criticism from newspapers and leaders of other churches—including the founder of the Pentecostal Church of the Nazarene, P. F. Bresee, who believed that Holiness people were already baptized in the Holy Spirit and that the Azusa tongues were not from God.

But some of the harshest criticism came from inside the little mission, with the mother church splitting because of personality clashes, fanaticism, doctrinal differences, and racial separation.

It was said that some whites left because the blacks had a lock on the leadership. Seymour, proving that he was no more perfect than his critics, reportedly asked the Hispanics to leave, and later wrote by-laws that prevented anyone except African-Americans from holding office in the mission. The often-quoted line that "the color line was washed away in the blood" was true in practice for only a short time.

Through the early months of the revival, Seymour gave credit for the movement's origins to Charles Parham and said that Azusa was an extension to the Midwest Apostolic Faith. Expecting a visit from Parham, Seymour wrote, "He was surely raised up of God to be an Apostle of this doctrine of Pentecost." But that "grand meeting" of October 1906 ended in a division that never fully healed.

Parham was shocked at what was being called spiritual manifestations. At what Seymour viewed as God-sent, Parham cringed with disgust, even labeling some adherents as spiritists.

|

|

"I sat on the platform in Azusa Street Mission, and saw the manifestations of the flesh, spiritualistic controls, [and] saw people practicing hypnotism at the altar over candidates seeking the baptism, though many were receiving the real baptism of the Holy Ghost. After preaching two or three times, I was informed by two of the elders, one who was a hypnotist…that I was not wanted in that place."

|

But though the founder and most prominent leader of Pentecostalism renounced it, Azusa Street eclipsed him as the center of the new movement.

|

y1849 –Sister White’s Vision

As we here read what Charles Fox Parham saw with his own eyes as he sat on the platform at the Azusa Street Mission – the hypnotism being practiced, some even from the pulpit, the outright Spiritism in the room along with what he saw as legitimate manifestations of the Holy Spirit also being practiced, along with an ongoing debate in the back of the room. As another noted “While some in the rear are opposing and arguing, others are at the altar falling down under the power of God and feasting in the good things of God. The two spirits are always manifest, but no opposition can kill, no power in earth or hell can stop God's work.“

We can be certain that indeed Ellen White had also seen in vision these very meetings, with all their flaws and shortcomings about 50 years before they occurred!

|

After some three years of daily, high intensity revival meetings, the Azusa Street Revival, still under Seymour's leadership, began winding down. When the crowds fell off, the mission soon looked like many other Pentecostal missions sprouting up in the Los Angeles area, with only sparse attendance.

Eventually, after Seymour's death in 1922 and his wife's in 1936, the mission closed and was razed. Only memories were left. But a new chapter in the history of the church had begun.

—Ted Olsen is assistant editor of Christian History. His principal source for this article was an unpublished manuscript by Wayne Warner, director of The Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center in Springfield, Missouri.

|

NEXT WEB PAGES IN SERIES:

On November 8, 2014 Pastor Erin Miller of the Foster

Seventh-day Adventist Church recognized some similarities of her fellow

church members with the 400 persons who gathered to meet the fleeing David

at the Cave of Adullam.

For Dr. Bob Holt's account--

Click Here!

or, if you prefer skip these pages for now and go

directly to

David's Dance before God's Holy Ark!

Quit and

Return to Main Index |

|